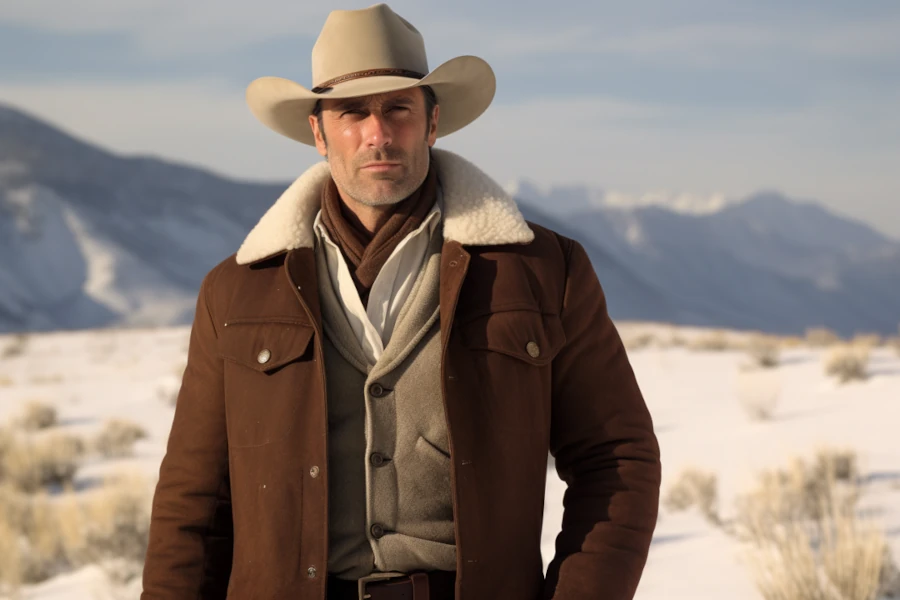

Sometimes a high-concept setting is all it takes to make a film. The Bad Batch imagines a world in which America fences off a large chunk of Texas desert and turns it into a penal colony. It doesn’t bother with explaining the political or cultural conditions that led to this outcome, nor does it need to.

The following summary contains pretty much the whole plot, so if you’re not into spoilers you may want to watch the film before reading this review. This movie cannot be analyzed without considering it from beginning to end, so a review without spoilers wouldn’t be particularly useful. Also, I’m just too lazy to be all fancy and create a more formal review that intricately weaves the criticism and summary together.

We follow a young woman named Arlen (Suki Waterhouse). Guards place her inside the penal zone and she aimlessly wanders about the merciless desert. Cannibals capture her, saw off a leg and an arm, cauterize the wounds, and keep her around for the next meal. At this point one can’t help but wonder if Arlen will not live long enough to be our protagonist, but she stages a desperate escape and a Good Samaritan (Jim Carey) drops her off at a friendly colony called “Comfort” run by an eclectic named “The Dream” who behaves like a cult leader (Keanu Reeves).

We skip ahead five months and Arlen has a prosthetic leg and appears to be well fed. She does not appear to be happy, but who could blame her? Comfort provides nothing beyond creature comforts. There are some sequences that suggest Arlen dreams of being physically whole again, but her motives are never really clear.

She settles on revenge, it seems. She takes a gun (why do they have guns here?), hobbles out of town, and shoots the first cannibal she can find right in front of the cannibal’s young cannibal daughter. The daughter, Honey (Jayda Fink), not knowing what to do, follows Arlen back to Comfort.

Arlen briefly attempts to take care of Honey. She buys her a rabbit. But the town has a giant party and Arlen drops acid and loses Honey. The Dream takes possession of Honey while Arlen wanders into the desert. While hallucinating in the desert, Arlen runs into Honey’s father, Miami Man (Jason Mamoa), who has figured out his daughter now resides in Comfort. Unaware of Arlen’s culpability, he enlists her to return Honey. He threatens her life, should she refuse, but it doesn’t really make sense because once she returns the armed citizens of Comfort would surely protect her. Miami Man can only leverage threats, so he does.

Although Arlen hobbled out to the desert the night before, for some reason getting back to Comfort is a real journey. A journey in which Arlen and Miami Man have some get-to-know-you moments. Miami Man protects Arlen a couple of times. When a stranger shoots Miami Man out of nowhere, Arlen leaves with the stranger back to Comfort. Miami Man appears to be shot directly in the heart, which should be fatal, but the Good Samaritan finds him and patches him up in no time.

Arlen looks for Honey. She even hands out flyers. No one has seen her. Finally, she happens to see Honey walking around with The Dream’s assault rifle-toting concubines. She goes to The Dream’s house. It’s a lavish mansion with a swimming pool. They have a weird conversation where The Dream explains that the drugs his concubines cultivate drive the entire economy of comfort. Who do they sell these drugs to? Why do they use money in this weird penal colony? Nevermind all that. The point is that they have things like running water because The Dream has made it so.

The Dream sees that Arlen is unhappy and this bothers him. He asks her what she wants. What could she possibly want, given their circumstances, that he hasn’t provided? She asks to be one of his concubines and he finds the proposal acceptable. Arlen is given a room.

Once a concubine takes Arlen to her room, she fishes a gun out of her prosthetic leg and takes the concubine hostage. She demands Honey. The Dream complies and she runs off to the dessert with Honey directly meeting up with a miraculously healed Miami Man. The father and daughter reunited, Miami Man tells Arlen to return to Comfort but she refuses, pushing herself into the family.

Honey says she’s hungry. She wants spaghetti because that’s what The Dream fed her. Miami Man, with nothing to feed his daughter but her pet rabbit, kills the rabbit. The film ends with the three of them eating the rabbit around a fire as Honey cries.

Nothing Makes Sense in The Bad Batch

There are two major problems with The Bad Batch. The first problem is that nothing makes sense. The whole penal colony idea just barely makes sense, and certainly a workable film could have been made with that idea. But none of the details make sense at all.

First of all, where does all the stuff come from? That question alone distracted me from the plot for large portions of the movie. How does The Dream make acid and grow marijuana with such limited resources? Why are the citizens of Comfort well armed and the cannibals only armed with melee weapons? Why don’t the citizens of Comfort just use their firearms to eliminate the much small society of menacing cannibals? Why don’t the cannibals eat the Good Samaritan? Why are the cannibals all so ripped and healthy when their diet is clearly deficient?

Practically every scene pulls you away from any suspension of disbelief because something nonsensical pops up.

Transgressive for the Sake of Being Transgressive

The more egregious sin The Bad Batch makes is meaninglessness. I thought for a long time about what this film means and I’m not sure I can come up with an answer. I don’t mean that in a good way, where it leaves you with something interesting to ponder, I mean that the filmmakers either failed to figure out a meaning for the film or they failed to articulate that meaning.

The Bad Batch clearly wants to be about something. The speech The Dream makes to Arlen, by design, is to be repudiated by her actions. He has found a way for people to live civilly, even in this hellish penal colony. So what if he has a harem and is grooming Honey to be a future member? It’s a lot better than living with those cannibals, right?

Arlen doesn’t think so despite being victimized by the cannibals. In fact, the ending suggests that she will take up cannibalism herself. Are the filmmakers trying to say that cannibalism is better than allowing a child to be raised by a perverted cult leader who grooms her to be a concubine? This may be a real choice in the fictional world of The Bad Batch, but in reality posing such a question amounts to no more than a false dichotomy.

I tried to give Ana Lily Amirpour, our screenwriter and director, the benefit of the doubt by thinking of these things as grave exaggerations. Perhaps she means that sexual abuse is so heinous that it might as well be cannibalism. But that’s just a crazy thought. That’s the type of 21st century thinking that can only result from never actually having to deal with things like crazy cannibals.

It seems useful to think of this world Amirpour has constructed as feudal. The Dream basically functions as a feudal lord. He has a castle, an army, and he exchanges protection and care to his peasants in exchange for labor. Feudal lords also groomed young girls to be future wives, and in most non-Christian societies had several (bigamy was illegal in Christian kingdoms, but surely perversions abounded). Were these not the very societies that paved the way to modernity?

The difference between a feudal state led by a man with questionable sexual proclivities and unstructured cannibals is that the cannibals have no path to improve themselves. Putting ethics aside, cannibalism causes neurodegenerative diseases and has most commonly been performed as an act of desperation during famines. Because humans host human diseases, cannibalism increases the odds of contracting any number of diseases. Although in my brief amount of research I was able to find many examples of cannibalistic societies throughout history, not one of them relied on human flesh as their primary source of nutrients. Most instances involved warfare, rituals, or famine. We don’t just recoil from cannibalism because it’s ethically egregious, cannibalism mortifies us because it simultaneously destroys the self and society.

This leads us to Honey. What fate would really be worse for her? Contracting HIV, prion diseases, or syphilis in a world without medical care? Or becoming the concubine of some weirdo at an inappropriate age? I would have to lean toward the latter. However, the choices that Amirpour has imagined seem so horrible that a mercy killing in the fashion of And Mice and Men may be called for.

It seems to me that Amirpour must not really know what she’s saying. Clearly she has no fidelity to reality throughout the entire film. It seems that she never did her research. She was too eager to tell the story to be bothered with the myriad details that make it impossible. These types of high-concept films are often vehicles for allegory or metaphor, but for the life of me I can’t figure out what comparison she might be drawing. I considered it as a metaphor for prison—but it’s literally a prison! In many ways it reminds me of books in the “transgressive” genre. The authors think of all sorts of horrible situations with which to torture their characters. When done well, there’s a point to it all. When done poorly, it just feels gratuitous. The Bad Batch is gratuitous.

Addendum

Out of habit I still check out Roger Ebert’s website to read the reviews after finishing a film. Now I wait until I’ve written my own review, to avoid the influence of another. Unfortunately, Roger is no longer with us and none of his replacements can compare. Sure, they’re much better writers than he ever was, but they act like writing reviews is a poetic act. I find it annoying and it distracts from the subject matter. It’s pretentious. But I digress.

The review for The Bad Batch largely aligned with my own opinion. Check it out if you want to read what I just wrote but done with a considerable amount more effort and skill. But then I noticed a second review. A sort of unofficial one without the badge of a star rating by Scott Derrickson. Titled, “Why The Bad Batch is one of the best films of 2017,” Derrickson attempts to answer the questions I posed above.

Derrickson sees a deep allegory, which I suspected Amirpour intended but apparently didn’t invest enough effort into decoding. The strong cannibals represent one half of our polarized America, those who prioritize strength and self-reliance and whose aggression endangers society. Rural people, I guess. The people of Comfort represent those fancy cities with their suffocating liberal values. While I don’t doubt this interpretation aligns with Amirpour’s intentions, I also don’t find it to be profound. Nor do I find his interpretation of Arlen’s actions to add any additional meaning to the film.

These are the types of allegories I would write as a teenager. Immature writers tend to conflate meaning with the profound, which makes allegory appealing to the novice writer. In many ways, the type of allegory reminds me of Edmund Spencer’s The Faerie Queene, a sixteenth century epic poem in which, at one point, a dragon attacks with all sorts of overt symbols of the Catholic Church. In fact, throughout the poem Spencer bombards the reader with anti-Catholic allegories that amount to little more than name calling.

For allegory to be successful, it must do three things. The Bad Batch only accomplishes the third (and barely).

- An allegory must be seamless with the narrative. You can’t justify a dumb plot that doesn’t make any sense by pointing out all the symbolism and hidden meaning. The plot must stand on its own, and the allegory compliments it.

- An allegory must not only make the story symbolize something in the real world, it must tell us something unique or interesting about the things it symbolizes. Like all forms of analogy, it must enlighten us to the subject at hand in ways more powerful than literalism.

- The allegory must be unlike the situation it represents. For instance, when I mentioned earlier that perhaps this was an allegory for prison. That would be a bad allegory because it is a prison. Analogy relies on drawing comparisons between unlike things.

So, basically, Derrickson’s pleas failed to move me and I still think The Bad Batch sucks.